10 June 2021, Writing – part xx531 Writing a Novel, more Turning the Telic Flaw into Plots

Announcement: Delay, my new novels can be seen on the internet, but my primary publisher has gone out of business—they couldn’t succeed in the past business and publishing environment. I’ll keep you informed, but I need a new publisher. More information can be found atwww.ancientlight.com. Check out my novels–I think you’ll really enjoy them.

Introduction: I wrote the novel Aksinya: Enchantment and the Daemon. This was my 21st novel and through this blog, I gave you the entire novel in installments that included commentary on the writing. In the commentary, in addition to other general information on writing, I explained, how the novel was constructed, the metaphors and symbols in it, the writing techniques and tricks I used, and the way I built the scenes. You can look back through this blog and read the entire novel beginning withhttp://www.pilotlion.blogspot.com/2010/10/new-novel-part-3-girl-and-demon.html.

I’m using this novel as an example of how I produce, market, and eventually (we hope) get a novel published. I’ll keep you informed along the way.

Today’s Blog: To see the steps in the publication process, visit my writing website http://www.ldalford.com/ and select “production schedule,” you will be sent to http://www.sisteroflight.com/.

The four plus one basic rules I employ when writing:

- Don’t confuse your readers.

- Entertain your readers.

- Ground your readers in the writing.

- Don’t show (or tell) everything.

4a. Show what can be seen, heard, felt, smelled, and tasted on the stage of the novel.

- Immerse yourself in the world of your writing.

These are the steps I use to write a novel including the five discrete parts of a novel:

- Design the initial scene

- Develop a theme statement (initial setting, protagonist, protagonist’s helper or antagonist, action statement)

- Research as required

- Develop the initial setting

- Develop the characters

- Identify the telic flaw (internal and external)

- Write the initial scene (identify the output: implied setting, implied characters, implied action movement)

- Write the next scene(s) to the climax (rising action)

- Write the climax scene

- Write the falling action scene(s)

- Write the dénouement scene

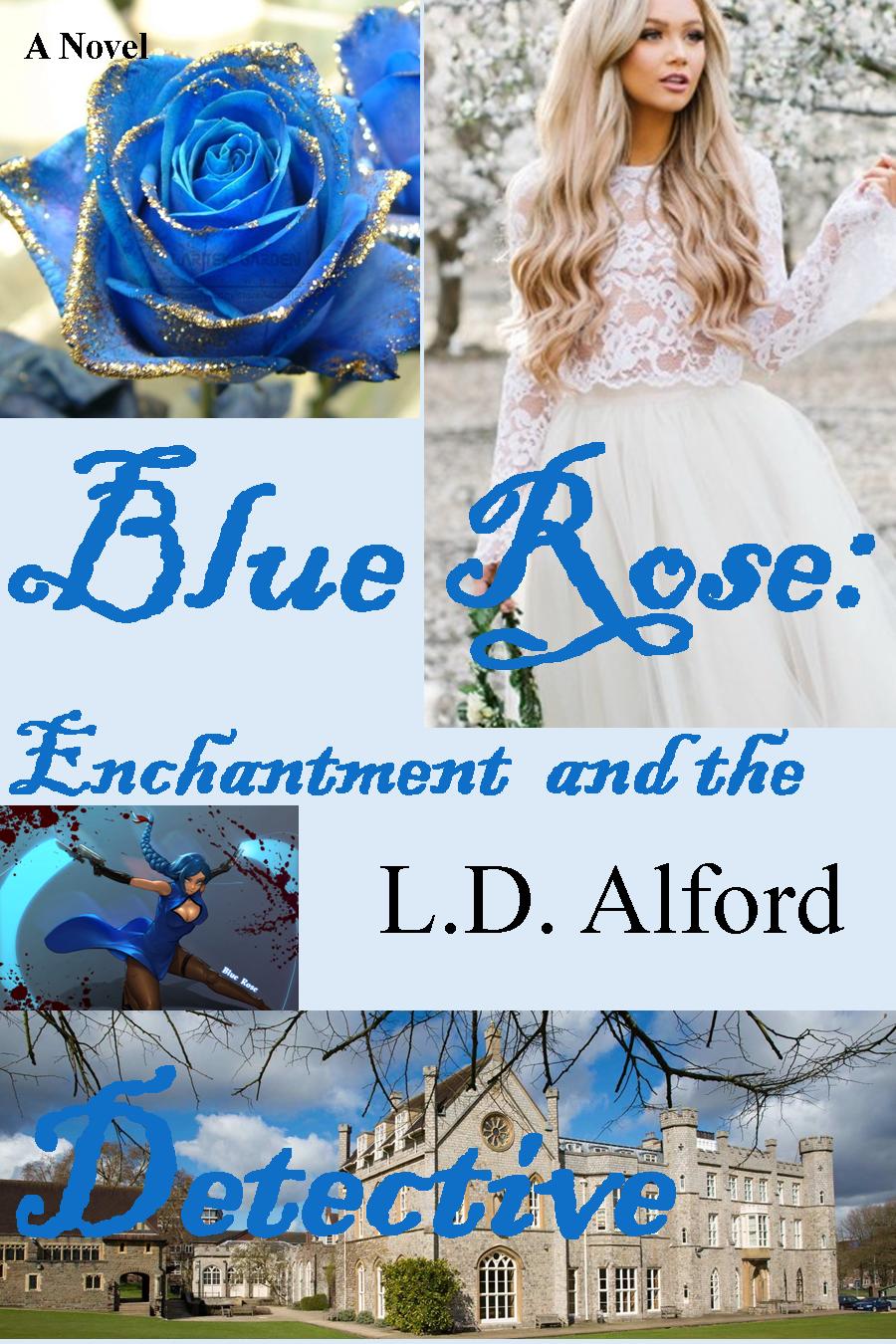

I finished writing my 29th novel, working title, Detective, potential title Blue Rose: Enchantment and the Detective. The theme statement is: Lady Azure Rose Wishart, the Chancellor of the Fae, supernatural detective, and all around dangerous girl, finds love, solves cases, breaks heads, and plays golf.

Here is the cover proposal for Blue Rose: Enchantment and the Detective.

The most important scene in any novel is the initial scene, but eventually, you have to move to the rising action. I am continuing to write on my 30th novel, working title Red Sonja. I finished my 29th novel, working title Detective. I’m planning to start on number 31, working title Shifter.

How to begin a novel. Number one thought, we need an entertaining idea. I usually encapsulate such an idea with a theme statement. Since I’m writing a new novel, we need a new theme statement. Here is an initial cut.

For novel 30: Red Sonja, a Soviet spy, infiltrates the X-plane programs at Edwards AFB as a test pilot’s administrative clerk, learns about freedom, and is redeemed.

For novel 31: Deirdre and Sorcha are redirected to French finishing school where they discover difficult mysteries, people, and events.

Here is the scene development outline:

- Scene input (comes from the previous scene output or is an initial scene)

- Write the scene setting (place, time, stuff, and characters)

- Imagine the output, creative elements, plot, telic flaw resolution (climax) and develop the tension and release.

- Write the scene using the output and creative elements to build the tension.

- Write the release

- Write the kicker

Today: Why don’t we go back to the basics and just writing a novel? I can tell you what I do, and show you how I go about putting a novel together. We can start with developing an idea then move into the details of the writing.

To start a novel, I picture an initial scene. I may start from a protagonist or just launch into mental development of an initial scene. I get the idea for an initial scene from all kinds of sources. To help get the creative juices flowing, let’s look at the initial scene.

- Meeting between the protagonist and the antagonist or the protagonist’s helper

- Action point in the plot

- Buildup to an exciting scene

- Indirect introduction of the protagonist

Ideas. We need ideas. Ideas allow us to figure out the protagonist and the telic flaw. Ideas don’t come fully armed from the mind of Zeus. We need to cultivate ideas.

- Read novels.

- Fill your mind with good stuff—basically the stuff you want to write about.

- Figure out what will build ideas in your mind and what will kill ideas in your mind.

- Study.

- Teach.

- Make the catharsis.

- Write.

The development of ideas is based on study and research, but it is also based on creativity. Creativity is the extrapolation of older ideas to form new ones or to present old ideas in a new form. It is a reflection of something new created with ties to the history, science, and logic (the intellect). Creativity requires consuming, thinking, and producing.

If we have filled our mind with all kinds of information and ideas, we are ready to become creative. Creativity means the extrapolation of older ideas to form new ones or to present old ideas in a new form. Literally, we are seeing the world in a new way, or actually, we are seeing some part of the world in a new way.

I’ve worked through creativity and the protagonist. The ultimate point is that if you properly develop your protagonist, you have created your novel. This moves us on to plots and initial scenes. As I noted, if you have a protagonist, you have a novel. The reason is that a protagonist comes with a telic flaw, and a telic flaw provides a plot and theme. If you have a protagonist, that gives you a telic flaw, a plot, and a theme. I will also argue this gives you an initial scene as well.

So, we worked extensively on the protagonist. I gave you many examples great, bad, and average. Most of these were from classics, but I also used my own novels and protagonists as examples. Here’s my plan.

- The protagonist comes with a telic flaw – the telic flaw isn’t necessarily a flaw in the protagonist, but rather a flaw in the world of the protagonist that only the Romantic protagonist can resolve.

- The telic flaw determines the plot.

- The telic flaw determines the theme.

- The telic flaw and the protagonist determines the initial scene.

- The protagonist and the telic flaw determines the initial setting.

- Plot examples from great classic plots.

- Plot examples from mediocre classic plots.

- Plot examples from my novels.

- Creativity and the telic flaw and plots.

- Writer’s block as a problem of continuing the plot.

Every great or good protagonist comes with their own telic flaw. I showed how this worked with my own writing and novels. Let’s go over it in terms of the plot.

This is all about the telic flaw. Every protagonist and every novel must come with a telic flaw. They are the same telic flaw. That telic flaw can be external, internal or both.

We found that a self-discovery telic flaw or a personal success telic flaw can potentially take a generic plot. We should be able to get an idea for the plot purely from the protagonist, telic flaw and setting. All of these are interlaced and bring us our plot.

For a great plot, the resolution of the telic flaw has to be a surprise to the protagonist and to the reader. This is both the measure and the goal. As I noted before, for a great plot, the author needs to make the telic flaw resolution appear to be impossible, but then it happens. There is much more to this.

Here is the list of classics that everyone should read. What I want to do is evaluate this list for the plots.

This is the plan. Let’s look at each novel and try to pull out the plot types, the telic flaw, and the theme of the novel. The ultimate point is we can glean plot ideas and types to add to our list. Part of this evaluation, we can try to identify the zero and the hero of the protagonist. All this might help us define plots and perhaps help us to develop plots for our own novels. This is kind of like looking at art as an artist and figuring out what makes a picture successful.

1 Pride and Prejudice – Jane Austen

2 The Lord of the Rings – JRR Tolkien

3 Jane Eyre – Charlotte Bronte

4 Dandelion Wine – Ray Bradbury – Best modern novel in English.

5 To Kill a Mockingbird – Harper Lee

6 The Bible – Most important book to understand Western culture.

7 Wuthering Heights – Emily Bronte

8 Nineteen Eighty Four – George Orwell

9 We The Living – Ayn Rand

10 Great Expectations – Charles Dickens

11 Little Women – Louisa M Alcott

12 Tess of the D’Urbervilles – Thomas Hardy

13 Dune – Frank Herbert

14 Complete Works of Shakespeare – better to see as plays

15 Rebecca – Daphne Du Maurier

16 The Hobbit – JRR Tolkien

17 The Cadwal Chronicles – Jack Vance

18 Catcher in the Rye – JD Salinger

19 The Green Pearl Novels – Jack Vance

20 Middlemarch – George Eliot

21 Gone With The Wind – Margaret Mitchel

22 The Great Gatsby – F Scott Fitzgerald

23 Bleak House – Charles Dickens

24 War and Peace – Leo Tolstoy

25 Starship Troopers – Robert Heinlein

27 Crime and Punishment – Fyodor Dostoyevsky

28 Grapes of Wrath – John Steinbeck

29 Alice in Wonderland – Lewis Carroll

30 The Wind in the Willows – Kenneth Grahame

31 Anna Karenina – Leo Tolstoy

32 David Copperfield – Charles Dickens

33 Chronicles of Narnia – CS Lewis

34 Emma -Jane Austen

35 Persuasion – Jane Austen

36 Atlas Shrugged – Ayn Rand

37 The Tale of Genji – Murasaki Shikibu

38 The House of Seven Gables – Nathaniel Hawthorne

39 The Scarlet Letter – Nathaniel Hawthorne

40 Winnie the Pooh – AA Milne

41 Animal Farm – George Orwell

42 Dracula – Bram Stoker

43 Til We All Have Faces – C.S. Lewis

44 Le Morte D’Arthur – Thomas Malory

45 The Woman in White – Wilkie Collins

46 Anne of Green Gables – LM Montgomery

47 Far From The Madding Crowd – Thomas Hardy

48 Ivanhoe – Sir Walter Scott

49 Lord of the Flies – William Golding

50 The Fountainhead – Ayn Rand

51 What Katy Did – Sarah Chauncey Woolsey under her pen name Susan Coolidge

52 A Little Princess – Frances Hodgson Burnett

53 The Secret Garden – Frances Hodgson Burnett

54 Sense and Sensibility – Jane Austen

55 The Jungle Book – Rudyard Kipling

56 Kim – Rudyard Kipling

57 A Tale Of Two Cities – Charles Dickens

58 Brave New World – Aldous Huxley

59 Beowulf – Unknown

60 The Odyssey – Homer

61 Of Mice and Men – John Steinbeck

62 Lolita – Vladimir Nabokov

63 The Moonstone – Wilkie Collins

64 The Maltese Falcon – Dashiell Hammett

65 Count of Monte Cristo – Alexandre Dumas

66 As I Lay Dying – William Faulkner

67 Jude the Obscure – Thomas Hardy

68 Robinson Caruso – Daniel Defoe

69 The Red Badge of Courage – Stephen Crane

70 Moby Dick – Herman Melville

71 Oliver Twist – Charles Dickens

72 Don Quixote – Miguel De Cervantes

73 Heidi – Johanna Spyri

74 Hans Brinker – Mary Mapes Dodge

75Ulysses – James Joyce

76 The Inferno – Dante

77 The Big Sky Country – Arlo Guthrie

78 Germinal – Emile Zola

79 Vanity Fair – William Makepeace Thackeray

80 The Black Arrow – Robert Louis Stevenson

81 A Christmas Carol – Charles Dickens

82 Treasure Island – Robert Louis Stevenson

83 The Gulag Archipelago – Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

84 The Miser – George Elliot

85 Madame Bovary – Gustave Flaubert

86 For Whom the Bell Tolls – Ernest Hemmingway

87 Tarzan – Edger Rice Burroughs

88 The Death of Socrates – Plato

89 Adventures of Sherlock Holmes – Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

90 I, Robot – Isaac Asimov

91 Heart of Darkness – Joseph Conrad

92 The Little Prince – Antoine De Saint-Exupery

93 Huckleberry Fin – Mark Twain

94 Watership Down – Richard Adams

95 Gulliver’s Travels – Jonathan Swift

96 Matilda – Roald Dahl

97 The Three Musketeers – Alexandre Dumas

98 The Canterbury Tales – Geoffrey Chaucer

99 Charlie and the Chocolate Factory – Roald Dahl

100 Les Miserables – Victor Hugo

101 The Once and Future King – T.H. White

102 The Deerslayer – James Fenimore Cooper

103 The Black Book of Communism – Various

104 Ben Hur – Lew Wallace

105 The Robe – Lloyd C. Douglas

106 The Pilgrim’s Progress – John Bunyan

107 The Histories – Herodotus

108 Lives – Plutarch

109 The Call of the Wild – Jack London

110 Stand on Zanzibar – John Brunner

111 The Shockwave Rider – John Brunner

112 The Aeneid – Virgil

This is what I did. I looked at each novel and pulled out the plot types, the telic flaw, plotline, and the theme of the novel. I didn’t make a list of the themes, but we identified the telic flaw as internal and external and by plot type. This generally gives the plotline.

Here’s the list of plots from the 112 classics in literature.

1. Redemption – 17i, 7e, 23ei, 8 – 49%

2. Detective or mystery – 56, 1e – 51%

3. Messiah – 10 – 9%

4. End of the World – 3 – 3%

5. War – 20 – 18%

6. Anti-war –2 – 2%

7. Revenge or vengeance –3ie, 3e, 45 – 46%

8. Revelation –2e, 64, 1i – 60%

9. Zero to hero – 29 – 26%

10. Romance –1ie, 41 – 37%

11. Achievement – 16e, 19ei, 4i, 43 – 73%

12. Article – 1e, 46 – 42%

13. Travel –1e, 62 – 56%

14. Coming of age –1ei, 25 – 23%

15. Progress of technology – 6 – 5%

16. Discovery – 3ie, 57 – 54%

17. Rejected love (rejection) – 1ei, 21 – 20%

18. Miscommunication – 8 – 7%

19. Love triangle – 14 – 12%

20. Betrayal – 1i, 1ie, 46 – 43%

21. Totalitarian – 1e, 8 – 8%

22. Blood will out or fate –1i, 1e, 26 – 25%

23. Psychological –1i, 45 – 41%

24. Horror – 15 – 13%

25. Magic – 8 – 7%

26. Mistaken identity – 18 – 16%

27. Money – 2e, 26 – 25%

28. Spoiled child – 7 – 6%

29. Children – 24 – 21%

30. Historical – 19 – 17%

31. Legal – 5 – 4%

32. Adultery – 18 – 16%

33. Illness – 1e, 19 – 18%

34. School – 11 – 10%

35. Self-discovery – 3i, 12 – 13%

36. Guilt or Crime – 32 – 29%

37. Anti-hero – 6 – 5%

38. Immorality – 3i, 8 – 10%

39. Proselytizing – 4 – 4%

40. Satire – 10 – 9%

41. Reason – 10, 1ie – 10%

42. Escape – 1ie, 23 – 21%

43. Knowledge or Skill – 26 – 23%

44. Camaraderie – 19 – 17%

45. Parallel – 4 – 4%

46. Allegory – 10 – 9%

47. Curse – 4 – 4%

48. Insanity – 8 – 7%

49. Fantasy world – 5 – 4%

50. Mentor – 12 – 11%

51. Prison – 2 – 2%

52. Secrets – 21 – 19%

We have a list of all the major plots from this list of classics in literature. The question is what can we do with it? This is the first step in evaluating our results. I took a percentage of the results based on the number of classics.

Modern writing is all about the Romantic—both Romantic protagonists and Romantic plots. This is where we are going and this is the focus of modern entertaining literature.

In the end, we can see there are just a few baseline plots that are characteristics of most classics. These are the revelation, achievement, and redemption plots. When I write these are baseline, I mean that they are overall plots that might also have a different plotline or other plots directly supporting them. Here’s what I mean exactly about each of these plots:

Redemption: the protagonist must make an internal or external change to resolve the telic flaw. This is the major style of most great modern plots.

Revelation: the novel reveals portions of the life, experiences, and ideas of the protagonist in a cohesive and serial fashion from the initial scene to the climax and telic flaw resolution.

Achievement: the novel is characterized by a goal that the protagonist must achieve to resolve the telic flaw.

I evaluated the list of plots and categorized them according to the following scale:

Overall (o) – These are the three overall plots we defined above: redemption, achievement, and revelation.

Achievement (a) – There are plots that fall under the idea of the achievement plot.

Quality(q) – These are plots based on a personal or character quality.

Setting(s) – These are plots based on a setting.

Item(i) – These are plots based on an item.

All of the plots we looked at fall into one of these five. Let’s do that:

Overall (o)

1. Redemption (o) – 17i, 7e, 23ei, 8 – 49%

2. Revelation (o) –2e, 64, 1i – 60%

3. Achievement (o) – 16e, 19ei, 4i, 43 – 73%

Achievement (a)

1. Detective or mystery (a) – 56, 1e – 51%

2. Revenge or vengeance (a) –3ie, 3e, 45 – 46%

3. Zero to hero (a) – 29 – 26%

4. Romance (a) –1ie, 41 – 37%

5. Coming of age (a) –1ei, 25 – 23%

6. Progress of technology (a) – 6 – 5%

7. Discovery (a) – 3ie, 57 – 54%

8. Money (a) – 2e, 26 – 25%

9. Spoiled child (a) – 7 – 6%

10. Legal (a) – 5 – 4%

11. Adultery (qa) – 18 – 16%

12. Self-discovery (a) – 3i, 12 – 13%

13. Guilt or Crime (a) – 32 – 29%

14. Proselytizing (a) – 4 – 4%

15. Reason (a) – 10, 1ie – 10%

16. Escape (a) – 1ie, 23 – 21%

17. Knowledge or Skill (a) – 26 – 23%

18. Secrets (a) – 21 – 19%

Quality (q)

1. Messiah (q) – 10 – 9%

2. Adultery (qa) – 18 – 16%

3. Rejected love (rejection) (q) – 1ei, 21 – 20%

4. Miscommunication (q) – 8 – 7%

5. Love triangle (q) – 14 – 12%

6. Betrayal (q) – 1i, 1ie, 46 – 43%

7. Blood will out or fate (q) –1i, 1e, 26 – 25%

8. Psychological (q) –1i, 45 – 41%

9. Magic (q) – 8 – 7%

10. Mistaken identity (q) – 18 – 16%

11. Illness (q) – 1e, 19 – 18%

12. Anti-hero (q) – 6 – 5%

13. Immorality (q) – 3i, 8 – 10%

14. Satire (q) – 10 – 9%

15. Camaraderie (q) – 19 – 17%

16. Curse (q) – 4 – 4%

17. Insanity (q) – 8 – 7%

18. Mentor (q) – 12 – 11%

Setting (s)

1. End of the World (s) – 3 – 3%

2. War (s) – 20 – 18%

3. Anti-war (s) –2 – 2%

4. Travel (s) –1e, 62 – 56%

5. Totalitarian (s) – 1e, 8 – 8%

6. Horror (s) – 15 – 13%

7. Children (s) – 24 – 21%

8. Historical (s) – 19 – 17%

9. School (s) – 11 – 10%

10. Parallel (s) – 4 – 4%

11. Allegory (s) – 10 – 9%

12. Fantasy world (s) – 5 – 4%

13. Prison (s) – 2 – 2%

Item (i)

1. Article (i) – 1e, 46 – 42%

Let’s start with the idea of an internal and external telic flaw. Then let’s provide it a wrapper. The wrapper is the plot.

If we have a protagonist, we have a telic flaw. In fact, we should have an internal and an external telic flaw. We want to take the telic flaw and turn it into an overall plot and plots.

In looking at the classics and most specifically, the plots in the classics, it became obvious that every novel contains more than one plot. In fact, all novels contain many plots that support the telic flaw resolution. This was unexpected for me. I just presumed that each novel just had a plot, but evaluation of plots in a novel showed us this just wasn’t true. What is true is there should be only one telic flaw in a novel and the various plots all work together to resolve the telic flaw. We also saw that there can be an internal and external telic flaw. These are usually resolved in the same climax.

I showed and charted the various plots we find in the first Harry Potty novel. These are listed below. All of these plot types and plots result in the resolution of the telic flaw of the first Harry Potty novel.

In Harry Potty you have these plots:

Overall (o)

1. Redemption (o) – 17i, 7e, 23ei, 8 – 49% – yeap, Harry must change and learn about wizarding or something.

2. Revelation (o) –2e, 64, 1i – 60% – yeap, the whole wizarding world

3. Achievement (o) – 16e, 19ei, 4i, 43 – 73% – yeap, Harry must defeat Voldermort.

Achievement (a)

1. Detective or mystery (a) – 56, 1e – 51% – yeap, Harry has to solve some mysteries

2. Revenge or vengeance (a) –3ie, 3e, 45 – 46% – yeap, presumed since Voldermort murdered Harry’s parents

3. Zero to hero (a) – 29 – 26% – yeap, Harry is a hero from supposed zero (not a very good one)

4. Romance (a) –1ie, 41 – 37% – yeap, very slight.

5. Coming of age (a) –1ei, 25 – 23% – yeap, presumed.

6. Discovery (a) – 3ie, 57 – 54% – yeap, all about magic.

7. Self-discovery (a) – 3i, 12 – 13% – yeap, coming of age is self-discovery

8. Reason (a) – 10, 1ie – 10% – yeap, the end climax is based in the use of magic, chess thinking, riding a broom, and figuring out what the philosopher’s stone can do.

9. Knowledge or Skill (a) – 26 – 23% – yeap, that’s magic.

10. Secrets (a) – 21 – 19% – yeap, everybody has a secret in the wizard world

Quality (q)

1. Messiah (q) – 10 – 9% – yeap, Harry is a messiah.

2. Betrayal (q) – 1i, 1ie, 46 – 43% – yeap, Longshanks gets betrayed and that turns the success of Griffindor.

3. Blood will out or fate (q) –1i, 1e, 26 – 25% – yeap, Harry was born to be the messiah.

4. Magic (q) – 8 – 7% – yeap, it’s all about magic.

5. Camaraderie (q) – 19 – 17% – yeap, with his friends.

6. Curse (q) – 4 – 4% – yeap, the mark and his power over Voldermort.

7. Mentor (q) – 12 – 11% – kinda, you get this more in the other novels, but Harry has his mentors throughout.

Setting (s)

1. War (s) – 20 – 18% – yeap, Voldermort is at war with the rest of the wizard world.

2. Travel (s) –1e, 62 – 56% – yeap, some travel to Hogswart and around.

3. Horror (s) – 15 – 13% – kinda, it’s low grade, but supposed to excite.

4. Children (s) – 24 – 21% – obviously

5. School (s) – 11 – 10% – duh

6. Parallel (s) – 4 – 4% – yeap, with the real world. This is a reflected worldview.

7. Fantasy world (s) – 5 – 4% – yeap, there ain’t no real magic out there.

Item (i)

Article (i) – 1e, 46 – 42% – yeap, the broom, the philosopher’s stone, the mirror

Here’s the question for us as authors. If we have a protagonist with his or her telic flaw (the telic flaw of the novel) can we plot shop to help write and improve our novel? You’d think the answer should be a resounding yes. The actual answer is a resounding meh. Most of the time, the protagonist and the setting determines large portions of the plots. This is really important to understand. Let’s start at the top.

1. Redemption (o) – 17i, 7e, 23ei, 8 – 49% – yeap, Harry must change and learn about wizarding or something.

2. Revelation (o) –2e, 64, 1i – 60% – yeap, the whole wizarding world

3. Achievement (o) – 16e, 19ei, 4i, 43 – 73% – yeap, Harry must defeat Voldermort.

These are plots you should include in every modern novel. These are indicators of a Romantic approach and protagonist, plus they are just entertaining. Harry Potty at its basis is a coming-of-age novel. This means the protagonist must change to achieve the telic flaw. Thus, just by Harry being a child, we have a potential redemption plot. This doesn’t mean the author couldn’t screw it up, but even the slowest author should be able to eke some redemption out of a coming-of-age plot and plot setup.

Unless you are daft, you can’t miss the revelation plot either. Part of the entire power in Rowling’s entire setting is the revelation of the setting. She has an entire fantasy world parallel to the real one. There is just no way you can give up this opportunity.

Then there is the classic achievement plot. I wouldn’t even start a novel without some degree of achievement in the telic flaw or the plot. If you notice, the achievement plot is a direct reflection of the telic flaw while the redemption plot comes from the protagonist characteristics and the revelation comes out of the protagonist and the setting. That’s pretty nifty for novel writing, but not so great if we are plot picking. Let’s look at the second group.

1. Detective or mystery (a) – 56, 1e – 51% – yeap, Harry has to solve some mysteries

2. Revenge or vengeance (a) –3ie, 3e, 45 – 46% – yeap, presumed since Voldermort murdered Harry’s parents

3. Zero to hero (a) – 29 – 26% – yeap, Harry is a hero from supposed zero (not a very good one)

4. Romance (a) –1ie, 41 – 37% – yeap, very slight.

5. Coming of age (a) –1ei, 25 – 23% – yeap, presumed.

6. Discovery (a) – 3ie, 57 – 54% – yeap, all about magic.

7. Self-discovery (a) – 3i, 12 – 13% – yeap, coming of age is self-discovery

8. Reason (a) – 10, 1ie – 10% – yeap, the end climax is based in the use of magic, chess thinking, riding a broom, and figuring out what the philosopher’s stone can do.

9. Knowledge or Skill (a) – 26 – 23% – yeap, that’s magic.

10. Secrets (a) – 21 – 19% – yeap, everybody has a secret in the wizard world

Now, we are getting into some choices. Some are more obvious than others. The first is detective or mystery. In this case, we are mostly thinking of mysteries. I’d almost say this is evident from the setting and the protagonist. How in the world can you reveal a wizarding world without mysteries? I’m sure you could, but I wouldn’t write a modern novel without mysteries and secrets. Secrets is another plot type. I’d almost say both plot types (secrets and mysteries) come out of the setting and the protagonist. With a plain old kid, you might have to work to produce some mysteries or secrets, but with a magic kid whose parents were wacked by the antagonist, you can’t leave out either.

Revenge or vengeance plots might leave us some latitude for choosing except Harry’s parent were wacked by the antagonist. You can’t ever forget this. In this case, again, the protagonist determines the required plots—just like the telic flaw. I guess you could have reverse vengeance if Harry joined with the antagonist, but that would not be a comedy and Harry could not resolve the telic flaw.

The zero to hero plot is a big must have. You could leave this plot off, but that would also turn the novel into a tragedy, and it wouldn’t be entertaining. If you think a million kids who want Harry to succeed would be happy with a non-hero, you are fooling yourself. They might take matters into their own hands and you with it. I’ve written many times before about the basic zero to hero plot. It is the plot of the comedy. You discard it or ignore it at your peril.

In the end, we can figure out what makes a work have a great plot, and apply this to our writing.

Let’s start with the idea of an internal and external telic flaw. Then let’s provide it a wrapper. The wrapper is the plot.

The beginning of creativity is study and effort. We can use this to extrapolate to creativity. In addition, we need to look at recording ideas and working with ideas.

More tomorrow.

For more information, you can visit my author site http://www.ldalford.com/, and my individual novel websites:

http://www.ancientlight.com/

http://www.aegyptnovel.com/

http://www.centurionnovel.com

http://www.thesecondmission.com/

http://www.theendofhonor.com/

http://www.thefoxshonor.com

http://www.aseasonofhonor.com

fiction, theme, plot, story, storyline, character development, scene, setting, conversation, novel, book, writing, information, study, marketing, tension, release, creative, idea, logic